Pythagoras. You probably know him for that pesky triangle theorem from high school. But what if I told you that his real legacy isn’t geometry? It’s music.

Yeah, the same guy who gave us the Pythagorean Theorem also unlocked the mathematical foundations of harmony. He didn’t just think about numbers abstractly—he listened to them. And what he found was nothing short of astonishing.

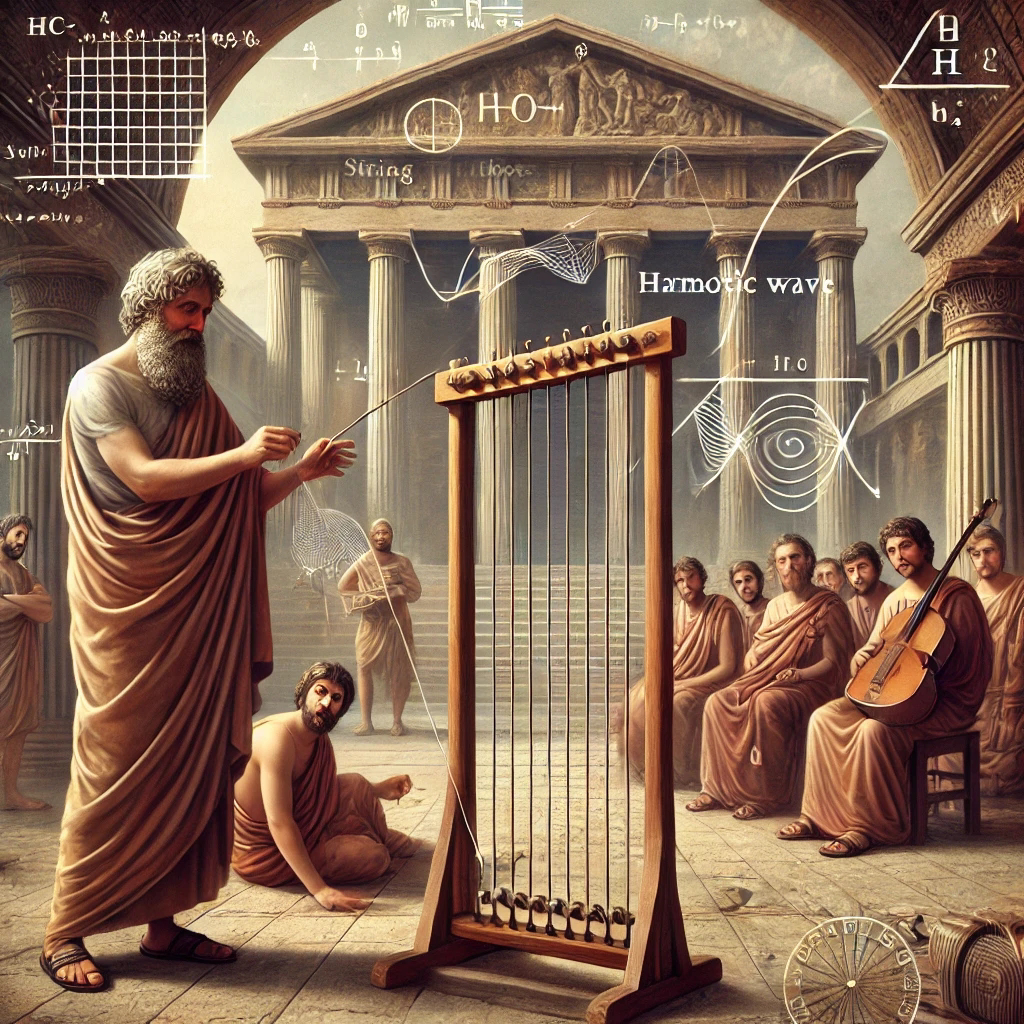

The Discovery: A String, a Hammer, and a Revelation

Legend has it that Pythagoras was walking past a blacksmith’s shop when he noticed something strange. The hammers striking the anvil produced different tones, and those tones had a kind of order to them.

That order wasn’t random—it was mathematical.

Being Pythagoras, he didn’t just shrug it off. He investigated. Eventually, he moved from hammers to something more precise: a single vibrating string.

The String Ratio Experiment

Pythagoras set up a simple experiment. He stretched a string across a frame (what we’d now call a monochord) and plucked it. It produced a tone. Then, he shortened the string to exactly half its length and plucked it again.

The result? The same note, but an octave higher.

He kept experimenting, dividing the string into different fractions and listening to the tones they produced. The results revealed something remarkable—certain ratios always created harmonious sounds.

The Core Ratios of Musical Harmony

Here’s what he found:

- 1:2 → The octave (e.g., C to high C)

- 2:3 → The perfect fifth (e.g., C to G)

- 3:4 → The perfect fourth (e.g., C to F)

- 4:5 → The major third (e.g., C to E)

- 5:6 → The minor third (e.g., C to E♭)

These aren’t just random numbers—they’re fundamental to how we hear and process music. If you play any instrument or even hum a tune, you’re engaging with these same ratios.

Why These Ratios Sound Good

Now, let’s get into why these specific ratios work.

When you pluck a string, it vibrates, sending waves through the air. Those waves hit your eardrum, and your brain interprets them as sound.

If two notes have vibrations that sync up in a simple, whole-number ratio—like 2:1 (octave) or 3:2 (perfect fifth)—the waves reinforce each other. Your brain perceives them as pleasant and stable.

On the other hand, if the ratio is more complex (like 17:12), the waves clash, producing dissonance. It’s why some note combinations sound jarring.

The Birth of the Pythagorean Scale

Pythagoras used these ratios to construct what became known as the Pythagorean Scale—the first structured attempt at a musical tuning system based on math.

It was built entirely on pure fifths (2:3 ratio). Starting from a base note and stacking perfect fifths, you cycle through a set of notes that form a scale.

The major problem? This system doesn’t fit neatly into the kind of tuning we use today (equal temperament). But for centuries, it was the gold standard.

From Pythagoras to Modern Music

The fact that music is built on mathematical relationships is still true today, whether you’re playing Beethoven, jazz, or EDM.

Western music eventually moved away from Pythagorean tuning toward equal temperament (dividing the octave into 12 equal parts). This shift wasn’t about math being wrong—it was about making music more flexible across different keys.

But the Pythagorean legacy remains:

- Every guitar fretboard is a direct descendant of his monochord.

- Every piano keyboard relies on ratios he identified.

- Every music theory textbook still traces harmony back to his discoveries.

The Deeper Implication: The Universe as Music

For Pythagoras, this wasn’t just about music. He believed these ratios weren’t arbitrary; they reflected the fundamental order of the universe.

He called this concept the “Harmony of the Spheres.”

The idea? Everything—planets, stars, even your very existence—is governed by mathematical harmony.

We now know planets don’t “hum” in a literal sense. But modern physics has uncovered patterns in nature that eerily resemble musical structures—resonance in atoms, orbital ratios in planetary motion, and even the vibrations of superstrings in quantum mechanics.

Maybe Pythagoras was onto something bigger than we ever imagined.

Final Thought

Next time you hear a song you love, remember: it’s not just music. It’s math. It’s harmony. It’s an ancient discovery that still shapes how we experience sound today.

Pythagoras didn’t just find numbers in music—he found music in numbers.

Stay curious.