Marcus Porcius Cato, better known as Cato the Younger, wasn’t the kind of man who bends. In an age of political corruption, backroom deals, and the slow, agonizing death of the Roman Republic, Cato stood firm. He wasn’t just a senator or a statesman—he was an idea made flesh, a symbol of Stoic virtue, and, ultimately, a tragic figure in the final act of Rome’s greatest political drama.

This is the story of a man who defied Julius Caesar, despised compromise, and chose death over surrender.

Born for the Republic

Cato was born in 95 BCE into a family with a legacy. His great-grandfather, Cato the Elder, had been a statesman and orator famous for his moral rigidity and his obsessive hatred of Carthage. The Younger Cato inherited that same stubbornness, but instead of Carthage, his great enemy would be tyranny.

From a young age, Cato was different. His Stoic philosophy wasn’t just a preference; it was the core of his identity. He embraced pain, discomfort, and discipline. As a child, he refused to cry even under extreme physical punishment. He lived simply, rejecting luxury despite being from one of Rome’s most distinguished families. To Cato, indulgence wasn’t just a personal weakness—it was a civic threat.

A Man of Principles in a Corrupt Republic

By the time Cato entered politics, the Roman Republic was rotting from the inside. The old systems were breaking down, and men like Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus were maneuvering for power, each trying to bend the system to their will.

Cato, however, saw things differently. To him, Rome wasn’t about power—it was about tradition, law, and the collective good. And he was willing to fight for it.

Cato vs. Crassus

Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome’s richest men, made a fortune off property speculation and fire brigades that would only put out flames if the owner agreed to sell. He was the epitome of corruption, using wealth to buy influence.

Cato wasn’t having it. As a quaestor (a financial officer of Rome), he ruthlessly investigated financial misconduct. He exposed corruption and forced Crassus’ cronies to return stolen money. He didn’t just talk about honesty—he enforced it.

Cato vs. Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, or Pompey the Great, was the Roman Republic’s most celebrated general. He was powerful, ambitious, and eager for more. When Pompey returned from his eastern campaigns in 61 BCE, he expected the Senate to grant him land for his veterans. It was the kind of political favor that powerful men always received.

Cato blocked it.

Not because he hated Pompey, but because Pompey wanted to bypass the system to get what he wanted. To Cato, the rule of law mattered more than any individual. He convinced the Senate to reject Pompey’s demands, forcing the great general to seek alliances elsewhere—most notably, with Julius Caesar and Crassus.

That decision would have massive consequences.

The Rise of Caesar and the Collapse of the Republic

Julius Caesar was everything Cato despised. Charismatic, opportunistic, and willing to manipulate the masses to gain power, Caesar understood the political game better than anyone. When he, Pompey, and Crassus formed the First Triumvirate in 60 BCE, Cato saw it for what it was: a direct attack on the Republic.

Unlike many senators who chose to work with Caesar, Cato resisted at every turn. He filibustered, he debated, he rallied opposition. When Caesar sought to pass land reforms that would increase his power, Cato spoke for hours to prevent a vote. When that failed, he stood against Caesar’s attempts to secure governorships and military command.

Caesar, frustrated, had Cato arrested and dragged out of the Senate. But instead of pleading, Cato walked out with his head held high. The public outcry was so great that Caesar had no choice but to release him.

For Cato, the Republic was worth any sacrifice.

Civil War: The Final Stand

When Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BCE, marching his army into Rome in direct defiance of the Senate, Cato knew what it meant—war. He joined Pompey and the senatorial forces, believing that they were fighting for the Republic.

Pompey, however, was no Cato. He was a pragmatist, not an idealist. When the Senate’s forces suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Pompey fled, eventually meeting his end in Egypt.

Cato, however, didn’t run.

He led what remained of the Republican resistance to North Africa, setting up in Utica. As Caesar closed in, his allies urged him to negotiate, to save his life. But for Cato, living under tyranny was not an option.

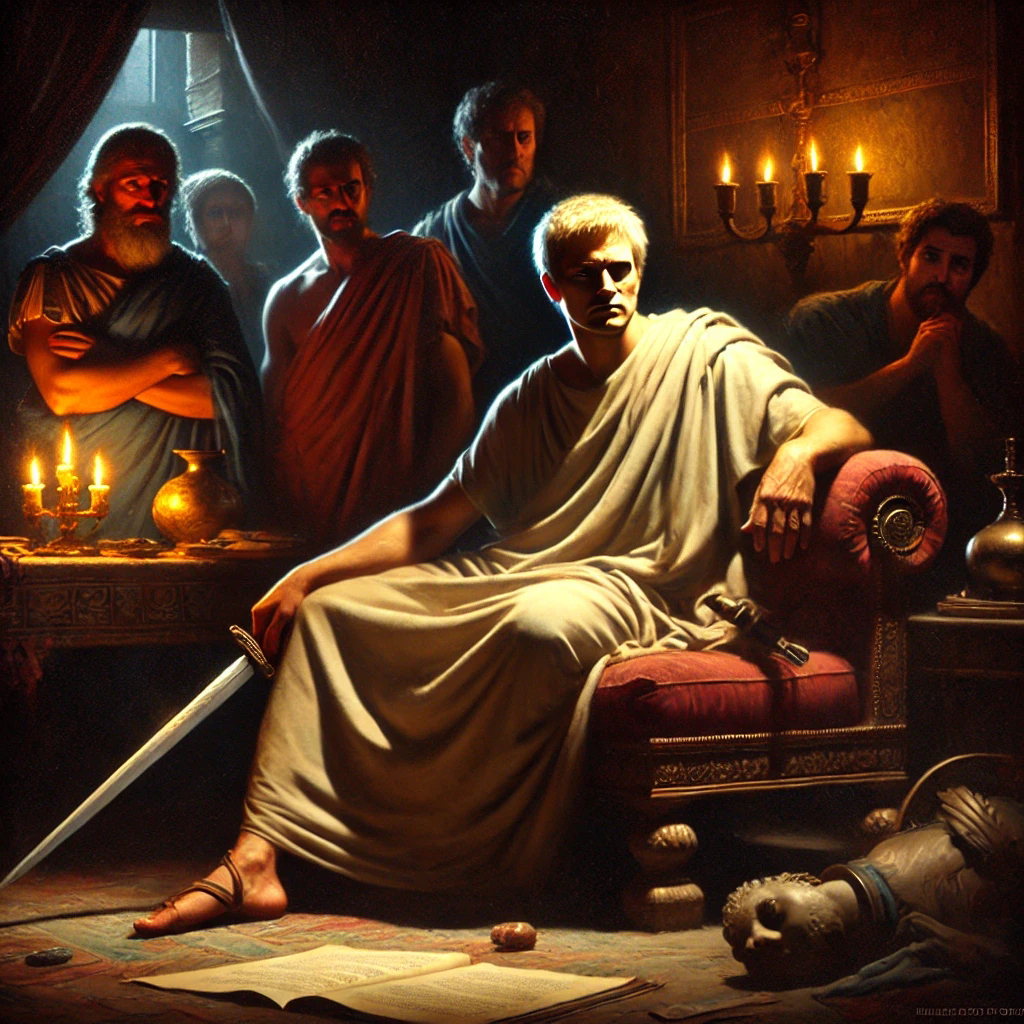

Cato’s Death: A Stoic Exit

On the night before Caesar’s army arrived, Cato dined with his friends, discussed philosophy, and recited passages from Plato’s Phaedo, a dialogue on the immortality of the soul.

Then, he went to his room, took his sword, and attempted to end his life. The first attempt failed—his wound wasn’t fatal. His friends rushed in, trying to save him. But as soon as they left, he tore open the wound with his own hands, ensuring his death.

For Cato, surrender was never an option.

The Legacy of Cato

Julius Caesar reportedly lamented Cato’s death, wishing he could have spared him. But Cato didn’t want to be spared. He wanted to die as the last unbroken Republican.

His death was symbolic. It wasn’t just the end of a man—it was the end of an era. The Republic was gone, and within a generation, Rome would be an empire.

But Cato’s defiance lived on. Centuries later, his name became synonymous with resistance to tyranny. The American Founding Fathers, especially George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, admired him. Joseph Addison’s play Cato was a favorite among revolutionaries.

Cato’s story is a reminder that sometimes, standing for principles means standing alone. And sometimes, the fight is worth it, even if you lose.

Stay curious.