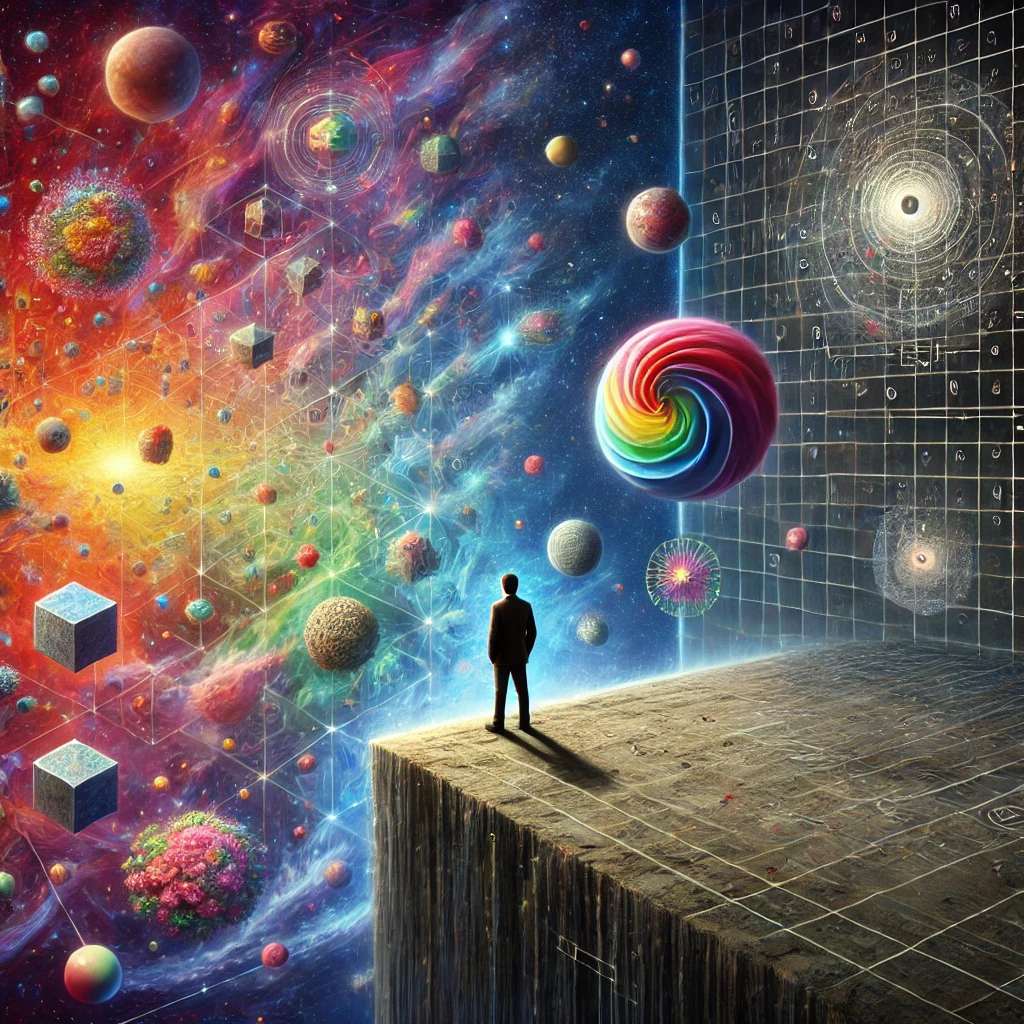

Immanuel Kant, one of the most influential philosophers of the Enlightenment, fundamentally reshaped how we think about reality and human perception. His distinction between the noumenal and phenomenal worlds is a cornerstone of his transcendental idealism, a theory that argues we never experience reality as it is in itself but only as it appears to us.

This concept is deceptively simple:

- Phenomenal world → The world as we perceive it, shaped by our senses and cognitive faculties.

- Noumenal world → The world as it is, independent of human perception, which we can never truly know.

Sounds straightforward, right? Not so fast. The implications of this idea are profound, challenging everything from scientific inquiry to metaphysical speculation. Let’s break it down.

What is the Phenomenal World?

Imagine you’re looking at a tree. It seems solid, green, and sways in the wind. But what you’re experiencing isn’t the tree in itself—it’s the tree as your senses and mind construct it.

Kant argues that the phenomenal world is structured by two key faculties:

- Sensibility (Space & Time) – Everything you perceive exists in space and time because that’s how your mind processes reality. If you stripped away your mind, there would be no space or time—at least, not as we understand them.

- Understanding (Categories of Thought) – The mind actively organizes sensory data using fundamental concepts like causality, unity, and substance. Without these, raw sensory input would be meaningless chaos.

Think of the mind like a lens that automatically shapes all incoming information. Everything you experience—the color of the tree, the feeling of the wind, the sound of rustling leaves—exists only as an interpretation filtered through these cognitive structures.

In short, the phenomenal world is reality as it appears to us, shaped by the way our minds structure experience.

What is the Noumenal World?

If the phenomenal world is how things appear, then the noumenal world is how things actually are, independent of human perception. Kant calls these “things-in-themselves” (Dinge an sich in German).

Here’s the catch: We cannot directly access the noumenal world. Our minds are hardwired to experience reality in a certain way—through space, time, and the categories of thought. That means whatever exists outside of our perception is fundamentally unknowable.

Imagine a bat trying to understand color. It can’t—its sensory apparatus isn’t built for it. Likewise, humans might be missing entire dimensions of reality simply because our cognitive faculties don’t allow us to perceive them.

Does the noumenal world contain things radically different from what we experience? Maybe. We just have no way of knowing.

Why Can’t We Know the Noumenal?

Kant argues that knowledge comes from experience structured by our minds. Since we only ever interact with the world through this structured experience, anything outside of it remains inaccessible.

Think of it like trying to see outside of your own eyes. Everything you look at is always framed by your perspective. You can’t step outside of your own consciousness to perceive things as they are without your mind shaping them.

For Kant, knowledge is always knowledge of appearances. The noumenal world is a necessary concept—it must exist because something underlies our experiences—but we can never grasp it directly.

The Problem with Metaphysics

Kant’s distinction between the noumenal and phenomenal world was a response to two opposing philosophical traditions:

- Empiricists (Locke, Hume): “All knowledge comes from sensory experience.”

- Rationalists (Descartes, Leibniz): “We can attain knowledge through pure reason.”

Both had problems. Empiricists couldn’t explain how we understand things like causality or mathematical truths. Rationalists thought reason alone could reveal deep truths about reality, but often ended up with speculative nonsense.

Kant’s answer? We only ever know the phenomenal world. The noumenal world might exist, but speculation about it is futile. That means traditional metaphysical claims—about God, free will, or the soul—can’t be proven or disproven.

This was a major philosophical shift. Kant didn’t deny the existence of God or free will, but he argued that they exist beyond the limits of human knowledge. You can believe in them, but you can’t prove them.

The Legacy of Kant’s Distinction

Kant’s split between the phenomenal and noumenal world changed the trajectory of philosophy. Here’s why it still matters:

- Limits of Science

- Science describes the phenomenal world, not the ultimate nature of reality. Every scientific law depends on human cognitive structures—space, time, causality—so they might not apply in the noumenal realm.

- Modern physics, especially quantum mechanics, echoes this idea. The observer affects the observed, and some aspects of reality seem unknowable.

- Philosophy of Mind

- If we only ever experience the phenomenal world, how much of what we think is “real” is just a construction of the mind?

- This directly connects to later thinkers like Schopenhauer (who took Kant’s ideas and made them even more radical) and 20th-century phenomenology.

- Skepticism about Metaphysical Claims

- If the noumenal world is inaccessible, how can anyone claim absolute knowledge about God, the soul, or the afterlife? Kant doesn’t deny these things but argues we can’t rationally prove them.

Common Misunderstandings

Some people take Kant’s ideas too far, assuming that since we can’t access the noumenal world, the phenomenal world is completely detached from reality. That’s not quite right.

Kant isn’t saying that the phenomenal world is an illusion—just that it’s a structured interpretation of reality. There is something real beyond our experience, but we just can’t know it directly.

A useful analogy: Imagine you’re wearing blue-tinted glasses. Everything you see appears blue, but that doesn’t mean the world isn’t real—it just means your perception is shaped by the lens through which you see it.

Conclusion: Living in the Phenomenal

Kant’s division between the noumenal and phenomenal is more than an abstract theory—it’s a challenge to how we think about reality. We live in the phenomenal world, bound by the limits of human perception, forever separated from things as they truly are.

But instead of seeing this as a limitation, Kant suggests it’s an opportunity. If we accept the limits of human knowledge, we can focus on what actually matters—how we experience life, how we construct meaning, and how we navigate a world that may be deeper than we can ever know.

Reality as it is may be forever hidden, but the reality we experience is the only one we’ve got. And according to Kant, that’s enough.